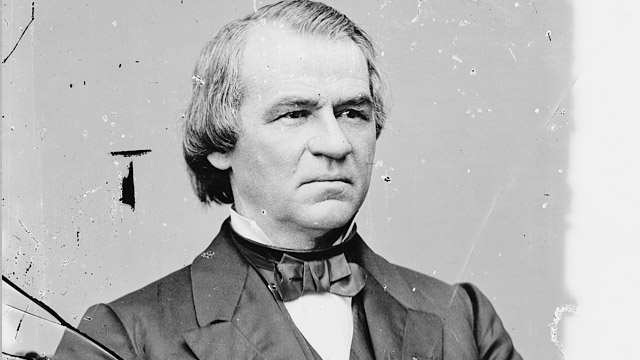

navneetdalal.com – The presidency of Andrew Johnson was one of the most turbulent and controversial in American history. A man of humble beginnings, Johnson ascended to the highest office in the land after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865. As the 17th President of the United States, he found himself in charge of a nation deeply divided after the Civil War. The Southern states had been defeated, and the Union was faced with the monumental task of rebuilding and integrating the South back into the fold. However, Johnson’s vision for the nation’s post-war future clashed sharply with the more radical Republicans in Congress, leading to a bitter power struggle that would define his presidency.

This article delves into the life and presidency of Andrew Johnson, examining his policies, the battles he fought with Congress, and the ultimate outcome of his leadership during the critical years of Reconstruction.

The Early Life of Andrew Johnson

Humble Beginnings and Rise in Politics

Born on December 29, 1808, in Raleigh, North Carolina, Andrew Johnson came from a poor family. His father, a humble gardener, died when Johnson was just four years old, leaving his mother to raise him. Largely self-educated, Johnson worked as a tailor in his early years, and it was through his trade that he became involved in local politics.

Johnson eventually moved to Greeneville, Tennessee, where he became a prominent figure. His political career began as a member of the Democratic Party, and he served in various local offices before being elected to the Tennessee state legislature. By the mid-1840s, Johnson’s political reputation had grown, and he served as a U.S. Congressman and Governor of Tennessee. Despite being a Southern Democrat, Johnson made his name as a staunch Unionist during the years leading up to the Civil War. His belief in preserving the Union, even at the expense of his Southern roots, would become a central theme of his later political career.

Andrew Johnson and the Civil War Era

A Unionist in the South

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Andrew Johnson’s loyalty to the Union put him at odds with many of his fellow Southerners. Tennessee seceded from the Union in 1861, and Johnson, as a leading figure in the state, was faced with a difficult decision. Despite his Southern background, he staunchly opposed secession and remained loyal to the Union cause. Johnson’s unwavering stance made him one of the few Southern politicians to support the North during the conflict.

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Johnson as the Military Governor of Tennessee, where he worked to enforce Union authority and protect Unionists in the state. Johnson’s efforts to keep Tennessee under Union control earned him the respect of many Northern politicians, though it also strained his relationships with Southern leaders who saw him as a traitor.

Ascension to the Presidency

In 1864, Lincoln, seeking to strengthen the Union war effort, selected Andrew Johnson as his running mate in the presidential election. Johnson, a Southern Unionist, was chosen to balance the ticket and appeal to the South. The pair won the election, and Johnson was inaugurated as vice president in March 1865.

Just over a month later, tragedy struck. On April 14, 1865, President Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, and Johnson was thrust into the presidency. The nation, still reeling from the Civil War, was now faced with the monumental task of rebuilding and reconciling with the South. Johnson, however, would soon find himself at odds with many in Congress, particularly the Radical Republicans, over how to handle the post-war reconstruction process.

Johnson’s Vision for Reconstruction

Lenient Policies and States’ Rights

Johnson’s approach to Reconstruction was based on his deep belief in states’ rights. He believed that the Southern states, which had seceded from the Union, should be quickly reintegrated into the United States without harsh penalties. His policies reflected his view that the Southern states had never legally left the Union, and that they should be restored to the Union as quickly as possible, with as few restrictions as necessary.

In May 1865, Johnson issued a Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, which granted pardons to most former Confederates who took an oath of allegiance to the United States. The proclamation also allowed Southern states to establish new governments, with the only stipulation that they had to void the acts of secession and repudiate Confederate debts.

Johnson’s lenient policies were controversial, particularly among the Radical Republicans in Congress. They believed that the South should be thoroughly restructured before being allowed back into the Union and that African Americans should be granted full civil rights. Johnson, however, was resistant to the idea of granting African Americans the right to vote and did not push for comprehensive civil rights legislation. His reluctance to protect the newly freed slaves and his swift restoration of Southern power alienated many in Congress.

Black Codes and Growing Tensions

In the aftermath of the Civil War, many Southern states enacted the Black Codes, a set of laws designed to limit the freedoms of African Americans. The Black Codes effectively sought to maintain a system of racial subjugation and prevent freedmen from enjoying the full rights of citizenship.

Johnson’s failure to address these codes or challenge their implementation led to mounting tensions with Congress. The Radical Republicans were outraged by the Black Codes and the slow pace of change in the South. They argued that the federal government needed to step in and guarantee the civil rights of African Americans, as the Southern states were not doing so on their own.

Clash with Congress

Radical Republicans and Johnson’s Opposition

The Radicals in Congress, led by figures like Thaddeus Stevens, Charles Sumner, and Benjamin Wade, became increasingly frustrated with Johnson’s refusal to support civil rights legislation. The Radicals were committed to securing equality for freedmen, and they believed that the Southern states should be subjected to strict terms in order to rejoin the Union. Johnson’s leniency, in their view, allowed the Southern states to continue exploiting African Americans and undermined the nation’s commitment to equality.

In 1866, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, which sought to protect the rights of African Americans and override the Black Codes. Johnson vetoed the bill, arguing that it represented an unconstitutional expansion of federal power. However, Congress, led by the Radicals, overrode Johnson’s veto, marking the first time in U.S. history that a major piece of legislation was passed over a presidential veto.

In response to Johnson’s opposition, Congress also moved forward with the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship and equal protection under the laws to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including African Americans. Johnson campaigned against the amendment, but it was ratified by the states in 1868, further highlighting the growing divide between the president and Congress.

The Military Reconstruction Act

In 1867, after Johnson’s veto of the Civil Rights Act and the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress took a more assertive stance in controlling Reconstruction. They passed the Military Reconstruction Act, which divided the South into military districts and placed them under the control of Union generals. The act required the Southern states to rewrite their constitutions, guarantee the right to vote for African American men, and ratify the Fourteenth Amendment in order to be readmitted to the Union.

Johnson, once again, vehemently opposed the act, arguing that it infringed upon the rights of the states. His veto was overridden by Congress, further diminishing his power and authority. Johnson’s defiance of Congress led to an ongoing power struggle, with the Radical Republicans consolidating their control over Reconstruction.

The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

The Tenure of Office Act

As tensions between the president and Congress reached a breaking point, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867, which restricted the president’s ability to remove certain officeholders, particularly those who had been appointed by previous administrations. The law was seen as a way to limit Johnson’s influence and ensure that his Reconstruction policies could not be easily undone.

In 1868, Johnson attempted to remove Edwin M. Stanton, his Secretary of War, who was aligned with the Radical Republicans. Johnson’s dismissal of Stanton violated the Tenure of Office Act, and Congress moved forward with impeachment proceedings.

The Impeachment Trial

In February 1868, the House of Representatives passed articles of impeachment against Johnson, accusing him of violating the Tenure of Office Act and attempting to undermine the Reconstruction efforts of Congress. The case moved to the Senate, where a trial was held to determine whether Johnson should be removed from office.

The trial concluded in May 1868, and the Senate narrowly acquitted Johnson by a vote of 35 to 19, just one vote shy of the two-thirds majority needed to convict him. Johnson remained in office, but his presidency was irrevocably damaged, and his influence was significantly diminished.

The Legacy of Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson’s presidency remains one of the most controversial in American history. His efforts to restore the Southern states to the Union quickly and without significant punishment were at odds with the more radical elements of the Republican Party, who sought to secure civil rights for African Americans and fundamentally reshape the South.

While Johnson’s presidency did not lead to the immediate results that many had hoped for, his political struggles set the stage for the continued fight for civil rights in the years to come. His impeachment, though unsuccessful, highlighted the growing power of Congress in shaping the nation’s policies during Reconstruction.

Johnson’s legacy is one of conflict, division, and missed opportunities. His refusal to fully support civil rights for African Americans and his resistance to the Reconstruction policies of Congress left a lasting impact on the nation’s post-war recovery. Though he survived impeachment, Johnson’s presidency was ultimately overshadowed by the Radical Republicans’ efforts to build a more just and equitable nation.